Resilience in the Face of Life’s Difficulties

The other day while scrolling online, I stumbled across a meme that stopped me in my tracks. It was macabre in design — a grinning skull, dark shadows around it — with the words: “Death smiles at everyone. Only the veteran smiles back.”

At first, I brushed it off as one of those tough-guy slogans you’d expect to find on a T-shirt or coffee mug. But the more I thought about it, the more those words lingered. A veteran who has been anywhere close to the battlefield has stared death in the face. And here’s the truth: the veteran doesn’t have to actually make it into the foxhole to start reckoning with life’s deepest questions. Just the awareness of what might happen — of how fragile life can be — is enough to shift a person’s soul.

From Foxhole to Army Clerk

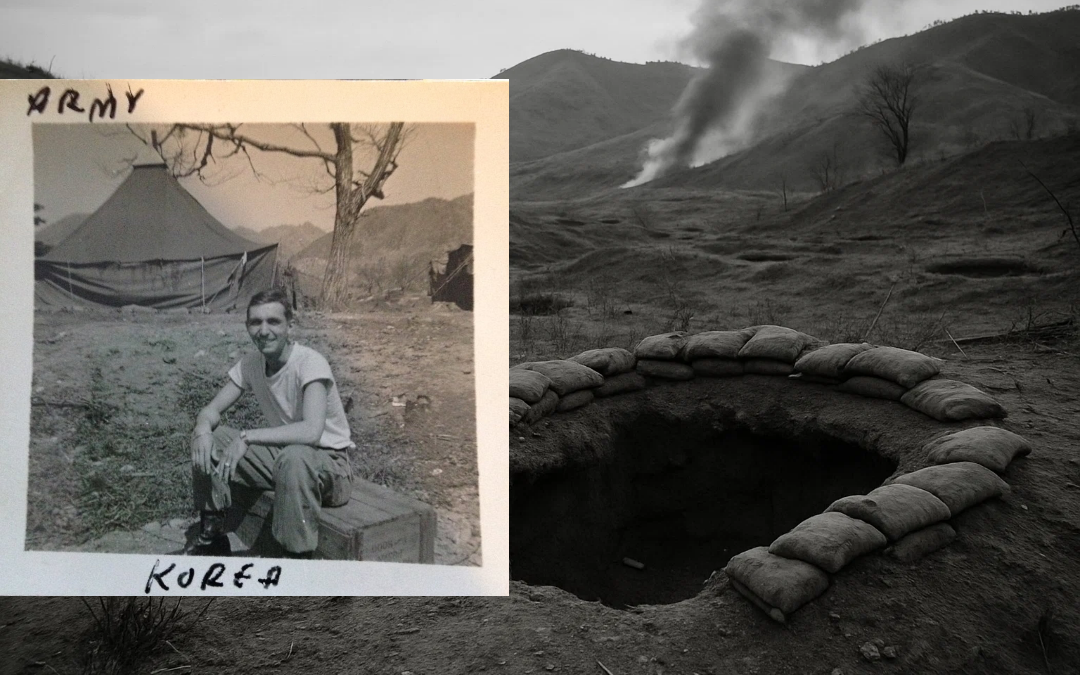

Of course, not everyone is cut out for physical conflict. Some men are built for the battlefield, and others are not. My own father was one of more than a million young men drafted to fight in the Korean Conflict in the nineteen-fifties. He was a quiet soul, slight in build, an academic type who in his youth had served faithfully as an altar boy at his parish. The idea of him charging with fervor out of a foxhole, rifle in hand, is hard for me to picture.

And yet, there he was — in his early twenties, sent overseas with the Army, and preparing for the possibility of bloody combat. He did his duty, but it was clear to those who knew him that soldiering wasn’t his nature. Then, as sometimes happens in war, a solution intervened.

One day he crossed paths with an officer in the Finance Corps — the army’s administrative support unit. The man was desperate for someone with typing skills, which were rare in those days. The job? Writing checks for the local “A-frame army,” men who handled non-combat tasks like building roads, transporting supplies to the front lines, and working in the kitchens. My dad eagerly volunteered. His ability to type, a skill many would have considered trivial, pulled him off the combat track and into an office tent.

A Typewriter and a Twist of Destiny

For years, I’ve reflected on that twist of destiny. Dad didn’t avoid danger out of cowardice — he simply served in another way. His contribution was quieter but still important, keeping the gears of the Army turning. That experience marked him. Perhaps it’s why he stressed the importance of typing for the five children in the family. I can still see myself at nine years old, perched on a pillow in front of a typewriter, pecking away at keys day after day.

Looking back, I realize he wasn’t just teaching me to type. He was teaching me resilience — that sometimes survival doesn’t come from brute force, but from using the gifts you already have. His story taught me that there are many ways to be a veteran, many ways to endure.

Veterans of Life

And really, isn’t that true of life as a whole? I don’t mean to minimize the sacrifices of veterans. But the battlefield isn’t always made of mud and gunfire. It can just as easily be the struggles of daily life: illness, grief, heartbreak, and the challenges that accumulate with age. Which is why that meme with the grinning skull rings true not only for military veterans, but for anyone who has lived long enough to collect scars and wisdom.

Because aren’t all older adults veterans in their own way? Veterans of work and family, of illness and recovery, of love and loss. Veterans of decades of change — in technology, in culture, in their own bodies. Life isn’t easy, and to reach old age is a kind of victory. It means you’ve faced battles — not always violent, but real nonetheless — and you’ve kept going.

The Calm That Comes With Age

One thing I sense from elders is a sense of calm about mortality that grows with time. Death is not welcomed, exactly, but neither is it feared in the way it was at forty or fifty.

Here’s a stoic perspective from the Roman philosopher and statesman Seneca:

“It takes the whole of life to learn how to live, and — what will perhaps make you wonder more — it takes the whole of life to learn how to die.”

(From his work, “On the Shortness of Life: Life Is Long if You Know How to Use It.”)

With experience comes perspective. You learn that fear isn’t a way to stop time. You learn that losses, as painful as they are, become part of you rather than the end of you. And you learn, perhaps most importantly, that joy is not found in outrunning death, but in walking steadily, even smiling, as you carry on.

Did you enjoy this article? Why not share it among your friends with the below buttons? Thank you.