Found in An Old Book

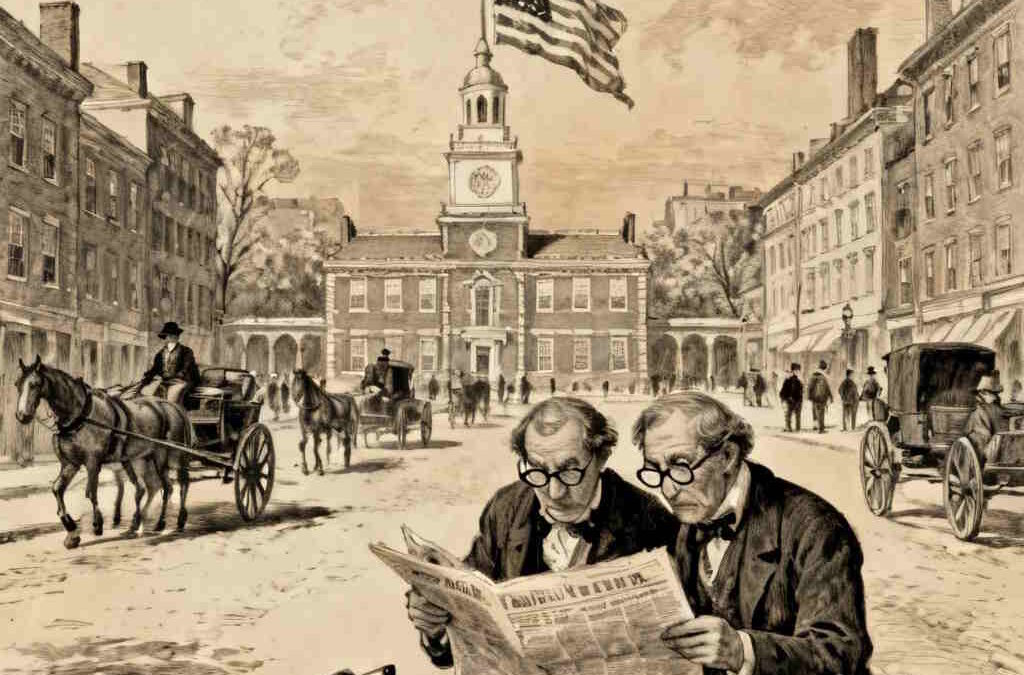

Since it is Thanksgiving, my thoughts return naturally to the early Pilgrims—those weary but hopeful travelers who paused amid hunger, grief, and uncertainty to give thanks to God for a hard-won harvest.

They tilled the soil with trembling hands, yet trusted with steady hearts. They could hardly have imagined that the fragile settlement they founded would become a vast and generous nation, abundant in resources and rich in spirit. Their gratitude, rooted in faith and family and the simple work of survival, still echoes across the centuries.

Whenever I reflect on the past—on people who lived, struggled, prayed, and persevered long before us—I find myself returning to an old Brumbaugh Standard Fifth Reader in my possession. Its browned cover, pages loosening at the seams, and childish pencil marks form a kind of timeworn tapestry. Its very wear gives it nobility. Within those yellowed leaves, faded by fingers long gone, lies a quiet treasury of wisdom.

Among its hidden gems is an essay by Joseph Story, the celebrated American jurist born in Massachusetts in 1779. The little anthology on my desk preserves his short essay “Our Duty to the Republic”—a piece so obscure that it cannot be found on the internet. That, in a way, makes it feel even more precious. It is a voice calling out from the past, urging us not to forget what makes a republic strong or—more importantly—what causes one to fall.

Once-Noble Republics

The author begins by reflecting on the noble republics of ancient Greece and Rome, whose glory was extinguished not by foreign spears but by inward decay. He writes of Greece that “she fell by the hands of her own people… It was already done by her own corruptions, banishments, and dissensions.” Thermopylae did not doom her. Marathon did not undo her. She was undone, already, by “her own corruptions, banishments, and dissensions.”

He continues with Rome, drawing the same solemn lesson. “A mortal disease was upon her vitals before Caesar had crossed the Rubicon.” Romans betrayed Rome long before legions marched. “The legions were bought and sold,” Story warns, “but the people offered the tribute money.” It is a haunting reminder: when people grow careless with their responsibilities, liberty becomes a thing easily purchased—and quickly lost.

A Nation Unmatched

And then Joseph Story turns his gaze toward America—a young nation in his day, but one whose promise he believed unmatched. His rallying cry rings just as true now as it did then:

“We stand the latest, and if we fail, probably the last experiment of self-government by the people…. We are in the vigor of youth. Our growth has never been checked by the oppressions of tyranny. Our constitutions have never been enfeebled by the vices or luxuries of the Old World. Such as we are, as we have been from the beginning—simple, hearty, intelligent, accustomed to self-government and to self-respect.”

He reminds us furthermore what makes America not merely strong, but hopeful.

“The government is mild. The press is free. Religion is free. Knowledge reaches—or may reach—every home. What fairer prospect of success could be presented? What means more adequate to accomplish the sublime end?”

Story closes with a probing question that strikes like a bell:

“Can it be that America, under such circumstances, can betray herself? Can it be that she is to be added to the catalog of republics, the inscription upon whose ruins is: ‘They were, but they are not’?”

And then his plea: “Forbid it, my countrymen! Forbid it, Heaven!”

As I hold this fragile book in my hands, I cannot help but feel that Story’s warning belongs to us today as urgently as it did to his own generation. A nation is not preserved by power or wealth but by the virtues of its people—qualities born in the home, nurtured in family life, strengthened by faith, and proven in daily work and generosity. The Pilgrims understood this. Our grandparents understood this.

And I hope we understand it too.